Style Quarterly Magazine

+

Sneak Peek

| www.

stylequarterly.com t fStyle Quarterly Magazine

+

Sneak Peek

| www.

stylequarterly.com t fÉ

mile-Jacques Ruhlmann was born in Paris

on August 28, 1879 to Alsatian parents

that owned a painting and contracting firm.

Ruhlmann spent most of his youth learning

his father’s trade during which time he made contact

with several young architects and designers. These

contacts would be Ruhlmann’s first look into the

world of furniture.

In 1907 upon his father’s death, Ruhlmann took over

the family business. Around 1910, a newly married

Ruhlmann had his first experience designing furniture

for their new apartment. This was also the first year

in which he exhibited his furniture publicly. In 1919

he founded a separate interior design company with

Pierre Laurent; the company designed everything

from wallpaper to rugs, light fixtures and furniture.

His early designs reflected the Art Nouveau influence popular in France at

the turn of the century. Later his influences could be traced to architects and

designers creating innovative furniture in Vienna around the time of the First

World War.

Although his very early work was quite heavy, apparently influenced by the

Arts & Crafts Movement, by 1920 Ruhlmann made clear his distain for the

movement. In a magazine interview in 1920 he succinctly stated his case:

“A clientele of artists, intellectuals and connoisseurs of modest means is

very congenial, but they are not in a position to pay for all the research, the

experimentation, the testing that is needed to develop a new design. Only the

very rich can pay for what is new and they alone can make it fashionable.

Fashions don’t start among the common people. Along with satisfying a

desire for change, fashion’s real purpose is to display wealth.” He further

stated: “Whether you want it or not, a style is just a craze. And fashion does

not come up from humble backgrounds.”

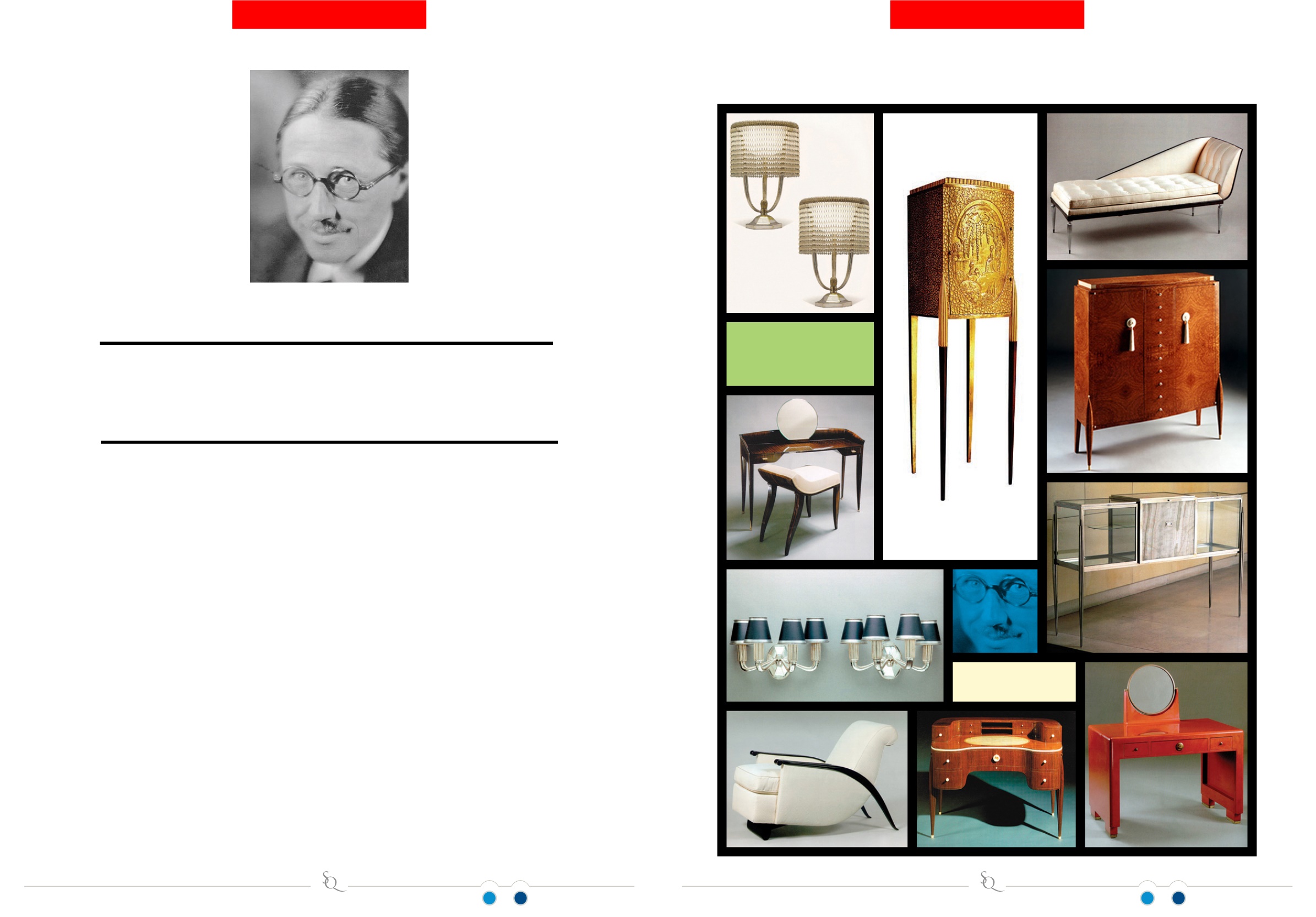

His strongest inspiration may have come from the classical design elements

and craftsmanship ideals found in 18th century furniture. Ruhlmann would

later shape these same ideals into what he called his precious pieces. These

pieces, most often occurring between 1918 and 1925 were his favorites. They

made use of the rarest woods such as Macassar ebony, Brazilian rosewood,

and amboyna burl, usually in combination with each other. Most of the forms

were very simple, making use of gentle, almost imperceptible curves. These

pieces were most often embellished with ivory; used for handles, dentil, feet,

and inlay. The ivory brought a static sense of control to the pieces that made

them unique, timeless and extremely elegant in form.

Contrary to popular thought, Ruhlmann did not work

with his hands and had no formal training in the

making of cabinets or furniture. In fact, all of his work

was done by outside cabinet shops until 1923 when he

assembled his own cabinetmaking shop.

By 1927, Ruhlmann’s shop had grown to two locations

employing 27 master cabinetmakers, four finishers, a

dozen upholsterers, a few apprentice cabinetmakers

and twenty-five draftsmen. While collaborating with

his cabinetmakers, he constantly pushed them to not be

confined by their craft. He would not accept that any

detail of his design could not be executed. Rather he

made his cabinetmakers start over and over until they

got it right, when he exclaimed “Don’t touch a thing,

it’s perfect.”

Ruhlmann’s work far exceeded the costly materials and consummate

workmanship that he touted. Although his pieces were exorbitant in price,

Ruhlmann admitted to a journalist: “Each piece of furniture that I deliver

costs me on average 20 or 25 percent more than what I charged for it. Over

the past trading year (1923) I have lost 300,000 francs net. The reason for me

to resist, to persist in creating furniture that costs me money instead of being

profitable, is that I still have faith in the future, and that I run another business

with safe return, and whose profits fill up the holes that I am digging in the

moon.”

Ruhlmann’s command over design and mastery of material combinations

yielded pieces of furniture that are historically incomparable. His formal

elegance made much of the work of his contemporaries appear bizarre in

form, and garish with respect to materials and color.

When Ruhlmann learned that he was terminally ill in 1933, he determined

to forever protect the name that he had built over a twenty-year period. In

his will, he stated that the company was to complete the orders that were

currently in-house, and then he ordered the dissolution of the company.

When examining Ruhlmann’s furniture, take notice of the subtle use of grain.

Ruhlmann was careful not to allow the figure of the wood to vie for attention

with the form of the furniture. His two favorite woods; Macassar ebony and

amboyna burl both create soft but striking background patterns, without

focusing attention on the wood itself. This allowed the veneers to support the

design details instead of competing with them. For more information on E.J.

Ruhlmann visit

www.ruhlmann.info.É.J. RUHLMANN

Master Art Deco Furniture Designer

1879 - 1933

“TO CREATE SOMETHING THAT LASTS,

THE FIRST THING IS TO WANT TO CREATE SOMETHING

THAT LASTS FOREVER”

ÉMILE-JACQUES RUHLMANN FURNITURE DESIGNS